Source: own picture

Area: 5 769,784 sqkm

Inhabitants Distrito Federal: 3 094 325

Density: 537,1 hab/sqkm

Capital History of Brazil

Brazil is considered a country of superlatives and disparities, so it is hardly surprising that the capital city

Brasília is also in many regards exceptional even amongst other capital cities, boasting a wide range of unique

and fascinating dynamics. However, it is not only the processes that are currently at work in the city that are

important, but also the background and the history of Brasília (Anhuf & Coy 2017).

Brazil's first capitals were located on the coast: Salvador de Bahia was capital from 1549-1763 and Rio de Janeiro

from 1763 -1960. The core decision that a new Brazilian capital should abandon any coastal location and go far

inland was already made with the foundation of the Republic in 1889 (Struck 2017). The city was to be built in the

Midwest, towards the centre of the country. For generations, many places in the Midwest lived in almost complete

isolation because of the enormous distances between them and the coast, and because of the lack of transportation

links. These factors led to these regions developing a unique provincial lifestyle. In the 20th century, with the

construction of the new capital, this changed. Most importantly, it changed the perception of the Midwest. Even

though politically, economically, and culturally many activities still took place in the coastal zones of the

Southeast or Northeast, the Midwest was increasingly seen as a region which represented the “real, genuine”

Brazil. Brasilidade - Brazilian identity - was increasing in the rustic, rural, purist Midwest. More

attention was

paid to the interior (Coy 2013).

The growing population in the peripheral interior had to be managed and supplied. With agricultural colonization

and settlement advancing westward and the rubber boom in Amazonia, the relocation of the capital was also a

strategy towards securing resources militarily and establishing better economic and transportation links. It

therefore seemed essential to erect a new capital in the interior of the country as a centre of power and as an

economic hub.

Planning a New Capital

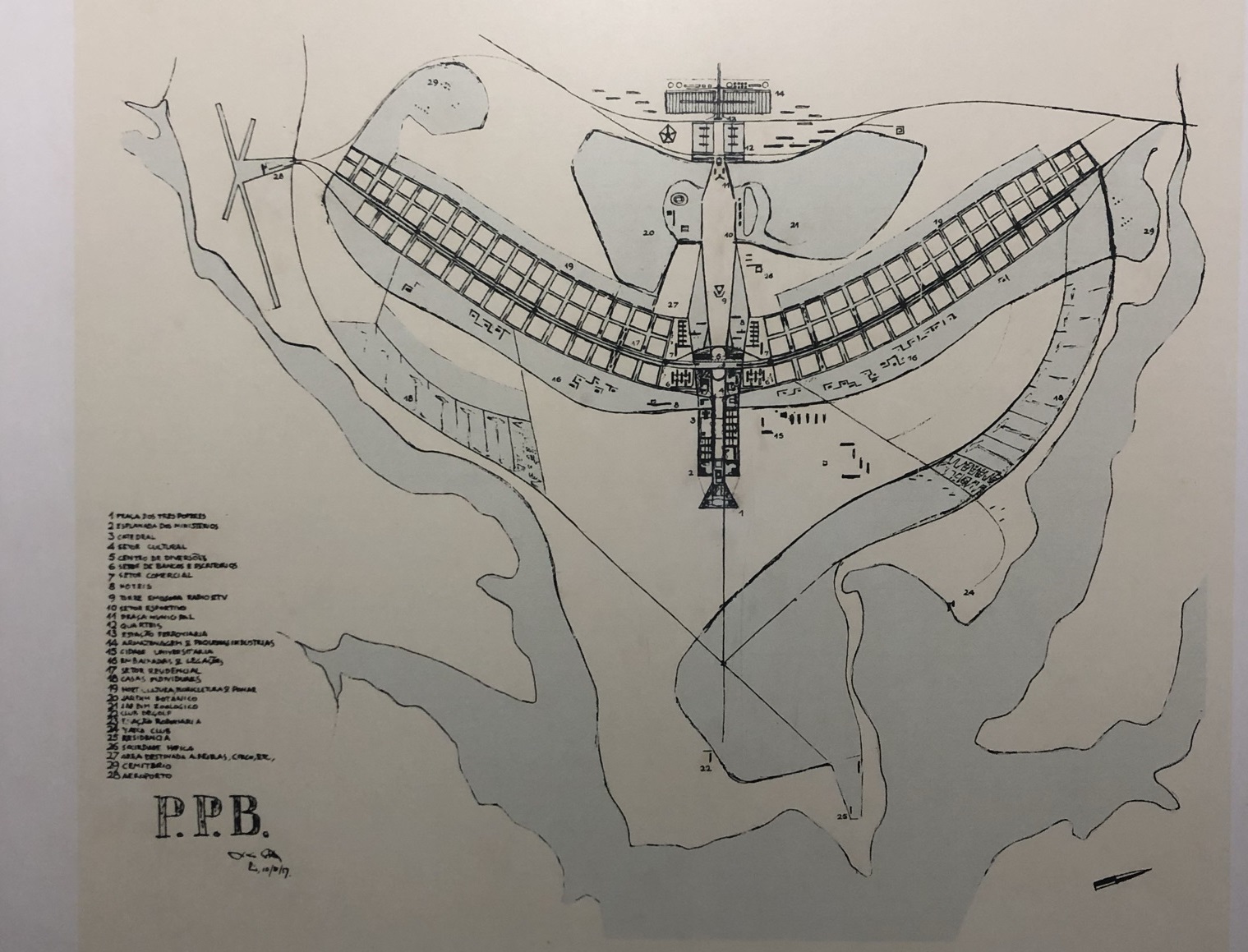

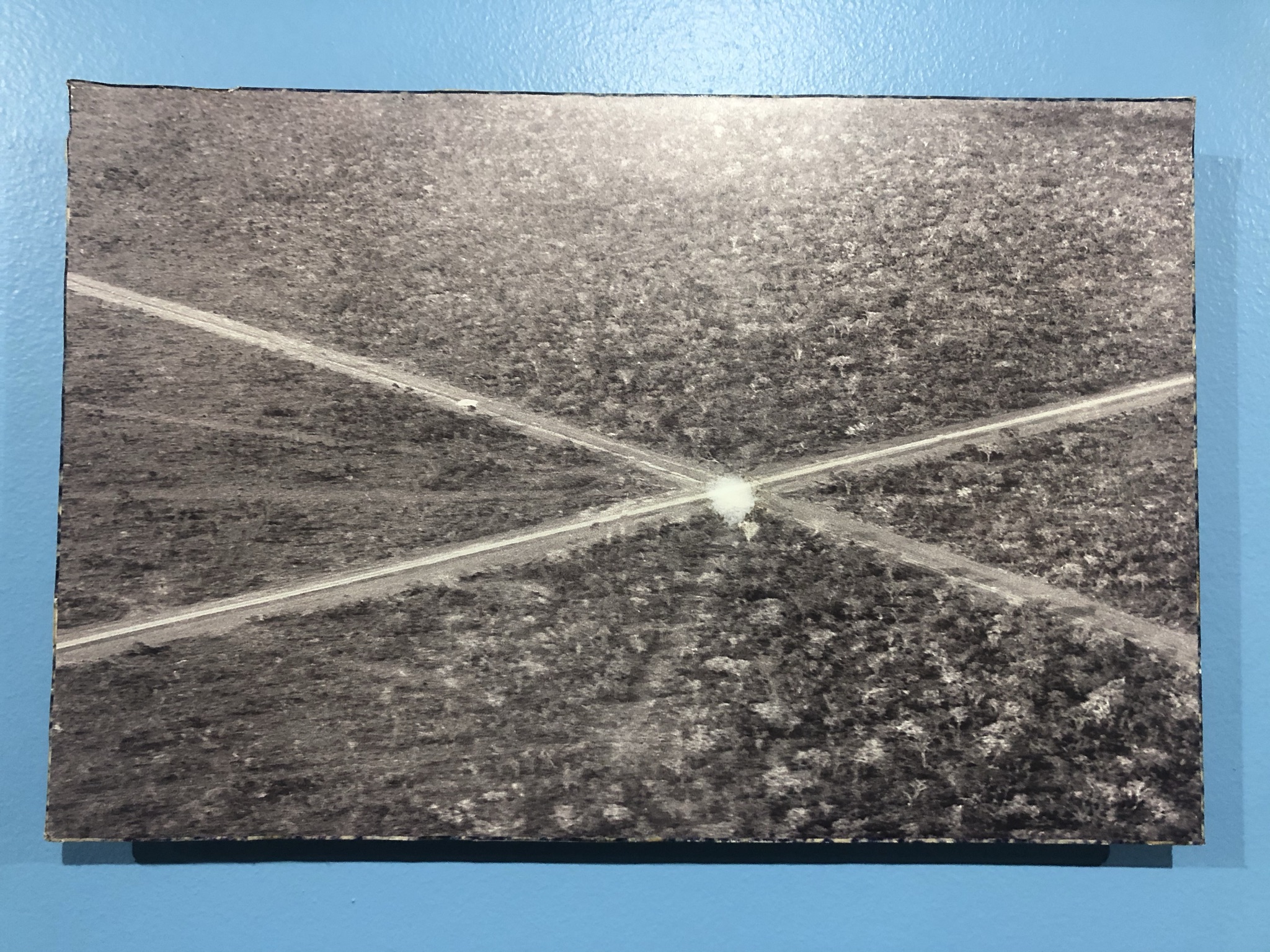

Where exactly the new capital was to be located, however, was long disputed, and it was not until 1948 that the final building site for Brasília was determined. The capital city project was closely linked to the policy of the transition to modernity pursued by President Juscelino Kubitschek (since 1956). Part of his agenda was technical progress, which was to be initiated by large-scale infrastructural projects. The project planning was a joint project of the urban planner Lúcio Costa and the architect Oscar Niemeyer (Struck 2017).Building Brasília was part of Kubitschek’s "fifty years of prosperity in five" plan. Designed in the shape of an airplane, the city was inaugurated as Brazil’s capital in 1960, after just 41 months of building. Immediately afterwards, legislation was passed to preserve the original layout, known as the Plano Piloto, restricting the growth of housing markets near the city centre (Dowall & Monkkonen 2007). The basic idea was based on the shape of the cross, formed by the intersection of the two main axes. On the monumental axis, political and cultural institutions are located, as well as the cathedral. At its end is the political centre: the Square of the Three Powers, the Presidential Palace, and the lake. The second axis is reserved for residential purposes with housing units - the superquadras - which were intended to form their own neighbourhoods and are equipped with central services. This model was intended to establish the utopia of an ideal city, via the concept of the functional city. Furthermore, the socialist paradigm, which proclaims equality for all citizens, was followed. At the same time, automobiles were prioritised, and the city was planned with a deliberately low population density. Brasília was promoted as the "City of Hope" and was intended to stand out as a vision for a new Brazilian society, freed from social inequality (Struck 2017).

Realizing the Plan

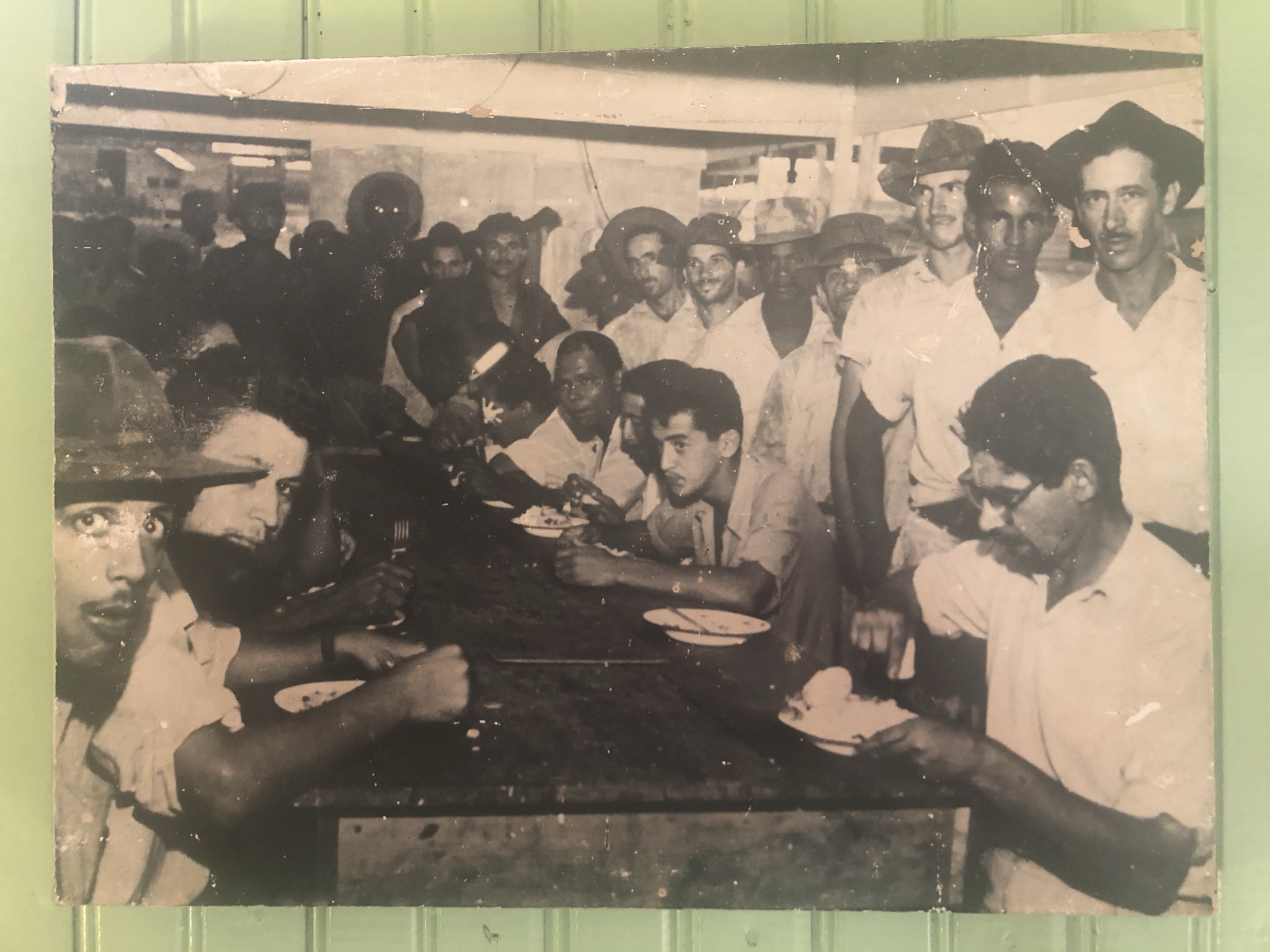

But how did the plan turn out? Even during the construction phase, spontaneous settlements sprang up around the Plano Piloto to house construction workers and basic service providers. Later, these settlements grew into satellite towns due to the lack of housing within the Plano Piloto structure (Struck 2017). Years later in December 1987, at the request of then-Governor José Aparecido de Oliveira, Brasília’s Plano Piloto was registered with UNESCO as a World Heritage site, making the area the first 20th century monument to achieve the protection of the United Nations. Despite the architectural significance of the city’s master plan, the rigid restrictions on urban development in Brasília have engendered perverse effects on the spatial distribution of the metropolitan area’s inhabitants and patterns of urban development.In this context, Brasília, and in broader sense Distrito Federal, still consists of an extremely static core and an exceedingly dynamic periphery (Dowall & Monkkonen 2007). Contemporary challenges thus include the lack of supra-regional governance, which is further complicated by the administrative division into municipalities and federal state (Costa & Lee 2019). Furthermore, Brasília faces issues like water resource management caused by land-use and landcover change (Lorz et al. 2012), housing shortage because of the imbalance between demand and stock (Samuels 2010) and also the problem of misconduct towards minorities, especially by disrespecting and degrading indigenous rights (Hanna et al. 2016). Even though most of the world societies perceive the climate change and its effects, Brasília doesn´t seem prepared for the climate change consequences and is far behind in terms of climate protection and adaptation and in terms of sustainable urban development (Ford et al. 2011). These issues can be seen for example in Brasília´s mobility management: There are hardly no pedestrian walkways or bike lanes, multi-lane motorways, etc. (Do Caromo Bezerra et al. 2017). Additionally, there are other challenges of daily life like accessibility of open spaces, maintenance of protected areas, management of supply and the creation of urbanity. Therefore, our research has been working on these topics among others (see topics) – including historical heritage and it´s influence on recent every-day life in Brasília and it´s surroundings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there are many advocates of Brasília who see great potential for the future in the city. One has also to consider the recent presidential elections and their impact on spatial and socio-economic development in Brasília as well as in Brazil. However, it can also be stated that the inequalities in the Brazilian population as a whole have not decreased as hoped. The essential social change has therefore failed to materialize, despite Brazil becoming economically stronger (Struck 2017). Brasília is therefore considered by some to be an artifact of modernity, possibly even a failed utopia, but nevertheless it remains an exciting city that offers much potential for research.Photo Gallery

References

Costa, Cayo; Lee, Sugie (2019): The Evolution of Urban Spatial Structure in Brasília: Focusing on the Role of Urban Development Policies. In: Sustainability 11 (2), p. 553. DOI: 10.3390/su11020553.

Coy, Martin (2013): Im Spannungsfeld zwischen globalem Wandel und regionaler Dynamik. Die Großregionen Brasiliens. In: Peter Birle (Hg.): Brasilien. Eine Einführung. Frankfurt am Main: Vervuert Verlagsgesellschaft (Bibliotheca Ibero-Americana, 151), p. 15–42.

Do Caromo Bezerra, Maria; Madsen, Marina & de Mello, Marco (2017): Mobility on modern urbanism: a study of Brasilia´s Plano Piloto. In: Procedia Environmental Sciences 37, p. 294-305.

Dowall, David E.; Monkkonen, Paavo (2007): Consequences of the Plano Piloto: The Urban Development and Land Markets of Brasília. In: Urban Studies 44 (10), p. 1871–1887. DOI: 10.1080/00420980701560018.

Ford, J. D.; Berrang-Ford, L.; Paterson, J. (2011): A systemic review of observed climate change adaption in developed nations. In: Climate Change 106, p. 327-336.

Hanna, Philippe; Langdon, Esther J.; Vanclay, Frank (2016): Indigenous rights, performativity and protest. In: Land Use Policy 50, p. 490-506.

Lorz, C.; Abbt-Braun, F.; Bakker, F.; Borges, P.; Börnick, H.; Fortes, L.; Frimmel, F. H.; Gaffron, A.; Hebben, N.; Höfer, R.; Makeschin, F.; Neder, K.; Roig, L. H.; Steininger, B.; Strauch, M.; Walde, D.; Weiß, H.; Worch, E. & Wummel, J. (2012): Challenges of an integrated water resource management for Distrito Federal, Western Central Brazil: climate, land-use and water resources. In: Environmental Earth Science 65, p. 1575-1586.

Samuels, Ivor (2010): Contemporary urbanism in Brazil: Beyond Brasília. In: Urban Design International 15, p. 129-132.

Struck, Ernst (2017): Brasília: eine Utopie als Repräsentation einer Supermacht. Von der Vision einer Stadt zum musealen Relikt. In: Dieter Anhuf (Hg.): Brasilien - Herausforderungen der neuen Supermacht des Südens. Mit 58 Farbabbildungen, 86 Farbbildern und 7 Tabellen. Passau: Selbstverlag Fach Geographie der Universität Passau (Passauer Kontaktstudium Geographie, 14), p. 23–33.